Win32/VirLock is ransomware that locks victims’ screens but also acts as parasitic virus, infecting existing files on their computers. The virus is also polymorphic, which makes it an interesting piece of malware to analyze. This is the first time such combination of malware features has been observed.

NOTE: Victims can restore their VirLock-infected files using our standalone cleaner, available for download.

Following the release of ESET's detailed white-paper covering our research into the TorrentLocker ransomware, we can now shed some light on a curious new member of the malware family extorting payments from infected users.

In most cases, ransomware is either of the ‘LockScreen’ type or the ‘Filecoder’ type. When a typical Filecoder encrypts files on the victim’s hard drive it usually doesn’t lock the screen, or otherwise prevent the victim to use their computer. The ransom notification can be displayed in several ways, such as displaying on the desktop wallpaper, by opening a text file, or – most commonly – inside a regular window (this was also the method used by Cryptolocker).

In some cases, ransomware takes a hybrid approach by both encrypting files and locking the screen by displaying a full screen message and blocking simple methods of closing it. An example of this behavior is Android/Simplocker – the first filecoder for Android.

In October we discovered a new, previously unseen approach – Win32/VirLock is ransomware that locks the screen and then not only encrypts existing files, but also infects them by prepending its body to executable files – thus acting as a parasitic virus. Sophos has also written about this interesting piece of malware on their blog.

We have observed a number of variants of the virus last month. This shows that the malware author has been keeping himself busy working on their creation. In fact, the virus looks somewhat like a malicious experiment and due to its polymorphic nature reminds us of viruses from the DOS era, such as the Whale virus. The way VirLock is implemented demonstrates a high level of programming skills, yet some of its functionality seems to be lacking logic, which is somewhat puzzling.

In this blog post we give a general overview of the virus behavior and explain what makes it polymorphic.

Win32/VirLock overview

A file infected with VirLock will be embedded into a Win32 PE file and the .exe extension appended to its name, unless it was already an executable file. When it is executed, it decrypts the original file from within its body, drops it to the current directory and opens it. The decryption methods are described later in the article. This behavior clearly sets it apart from typical filecoders.

VirLock then installs itself by dropping two randomly named instances of itself (not copies – the virus is polymorphic, so every instance is unique) into the %userprofile% and %allusersprofile% directories and adds entries in the Run registry keys under HKCU and HKLM so that they are launched when Windows boots up. These instances, which only contain the virus body without a host file to decrypt, are then launched. More recent variants of VirLock also drop a third instance that is registered as a service. This approach serves as a simple self-defense mechanism for the malware – processes and files get restored when they’re terminated or deleted.

The dropped instances are responsible for executing the actual malicious payloads.

One thread takes care of the infection of files. Win32/VirLock looks for host files by crawling through local and removable drives, and even network shares, to maximize its spreading potential. The file extensions intended to be infected differ between VirLock versions. An extension list from a recent sample contains the following: *.exe, *.doc, *.xls, *.zip, *.rar, *.pdf, *.ppt, *.mdb, *.mp3, *.mpg, *.png, *.gif, *.bmp, *.p12, *.cer, *.psd, *.crt, *.pem, *.pfx, *.p12, *.p7b, *.wma, *.jpg, *.jpeg.

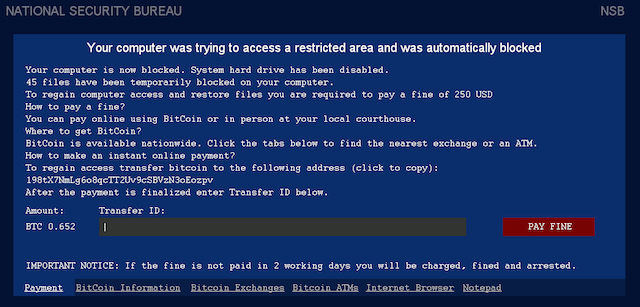

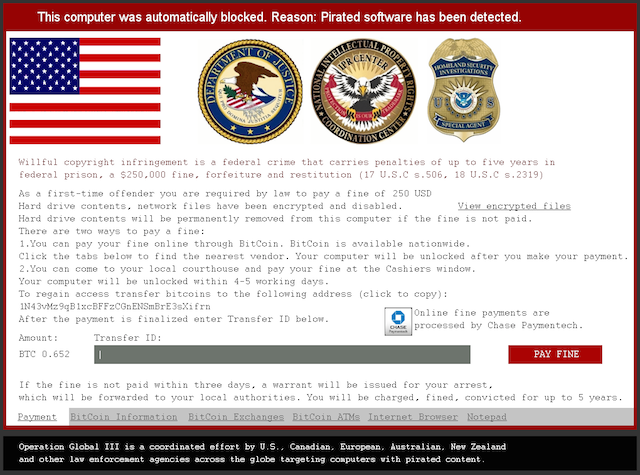

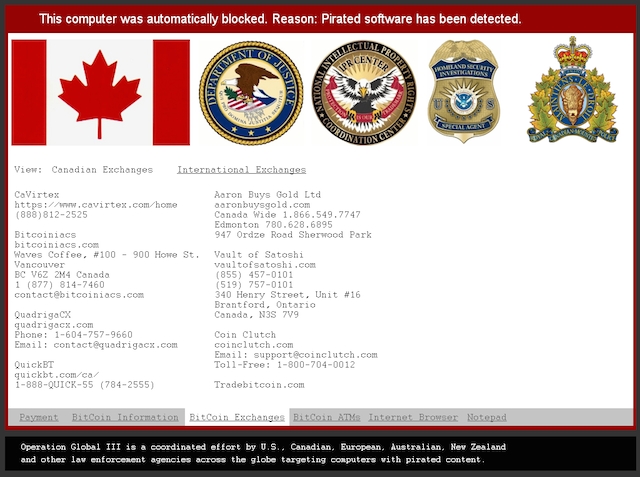

Another thread contains the lockscreen functionality – with typical protective measures like shutting down explorer.exe, the Task Manager, and so on – and displays the following ransom screen.

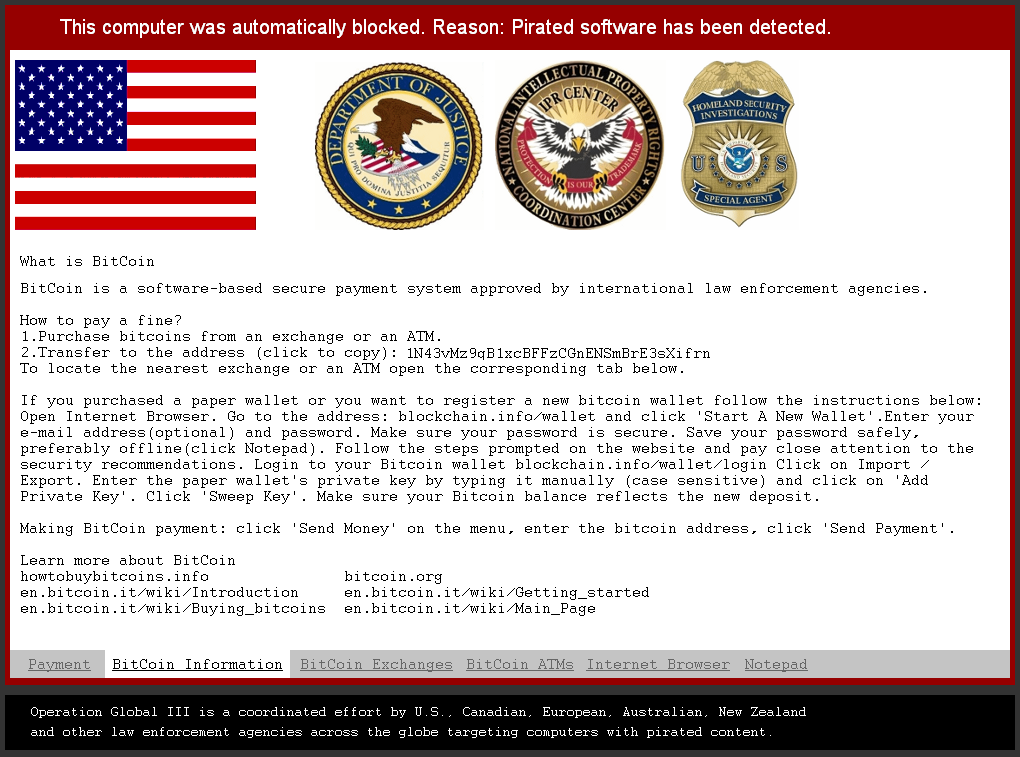

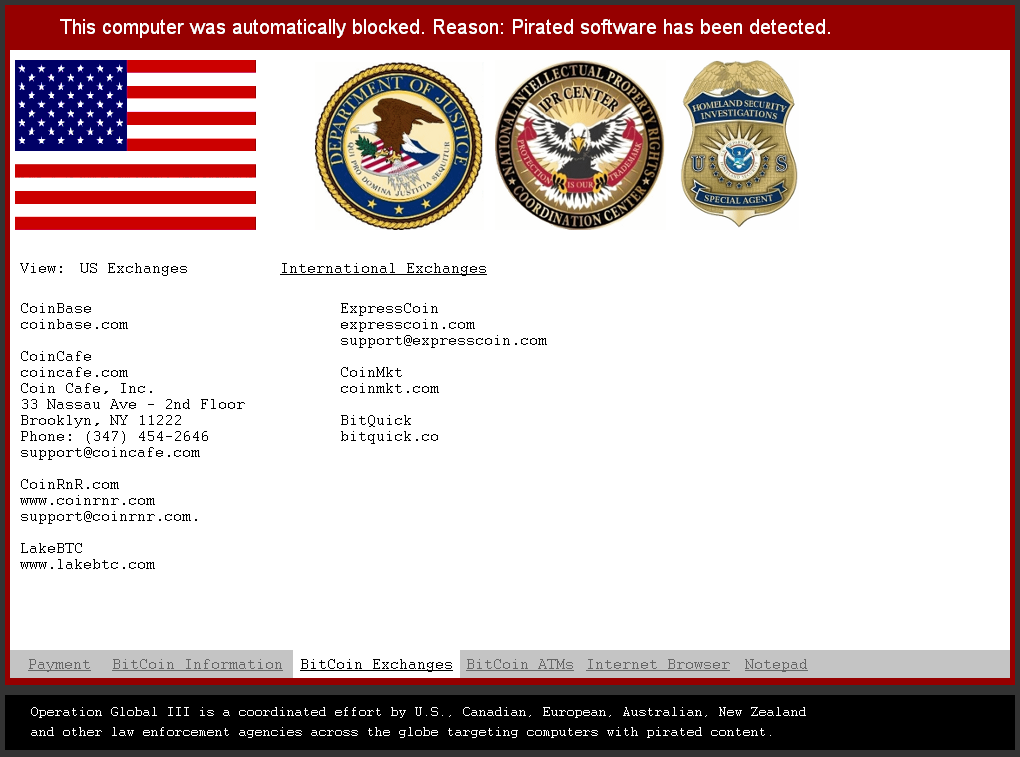

The ransom message is self-explanatory, so we will only cover the unique aspects. The screenshot above is from an earlier version, whereas the ones below are from a more recent one. The ransom is expected in Bitcoin and the malware author also gives clear instructions to victims who may not be familiar with the cryptocurrency. The lockscreen even allows victims to use an Internet browser and Notepad.

The screen locker is able to do some basic localization based on whether a connection attempt to google.com was redirected to either google.com.au, google.ca, google.co.uk, or google.co.nz and return value of the GetUserGeoID function. For those selected countries a different flag, Bitcoin exchanges and displayed currency will be shown. Even the ransom amount appears to be variable: either 150 USD or 250 USD / GBP / EUR / NZD / CAD / AUD.

VirLock polymorphism

From a technical point of view, probably the most interesting part about this malware is that the virus is polymorphic, meaning its body will be different for each infected host and also each time it’s executed. But before we explain how the code changes, we must take a look at the multiple layers of encryption it uses.

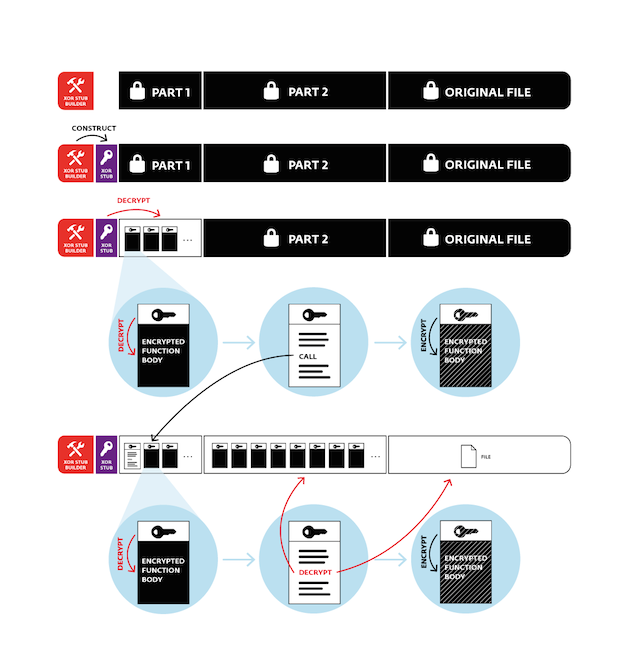

A simplified execution flow of earlier variants of Win32/VirLock is shown in the following infographic: When a Win32/VirLock binary is loaded into memory, the only unencrypted code is something we’ll call a XOR stub builder; all other code, data and the original file (if present – the same scheme applies to “stand-alone” VirLock instances) are encrypted.

When a Win32/VirLock binary is loaded into memory, the only unencrypted code is something we’ll call a XOR stub builder; all other code, data and the original file (if present – the same scheme applies to “stand-alone” VirLock instances) are encrypted.

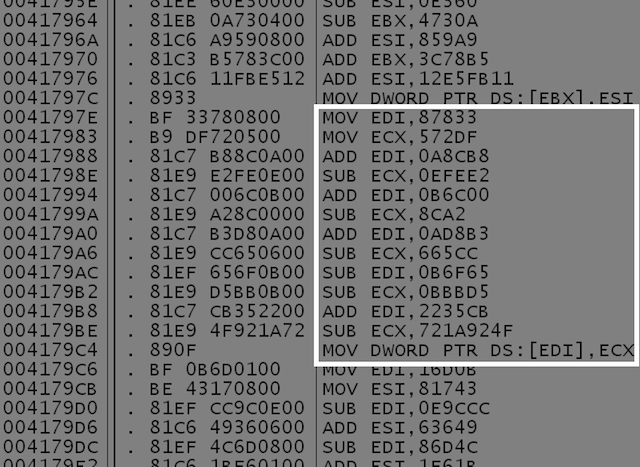

The following description of the XOR stub builder applies to older variants of Win32/VirLock. Newer variants employ a slightly more complex mechanism. The builder contains eight similar blocks like the one in the example code snippet below.

Each block consists of a specific calculated DWORD being written to a specific memory offset. The registers, operations (additions and subtractions) and constants are generated at random but produce the same desired output. Each of these blocks generates 4-bytes of the XOR stub that is exactly 32-bytes of assembly code. This stub is the next stage in Win32/VirLock’s execution.

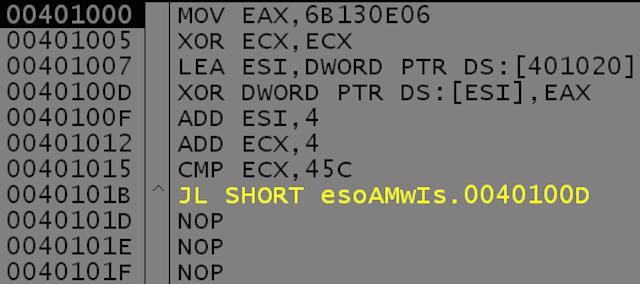

The XOR stub, as its name implies, will decrypt a smaller part (Part 1) of the actual VirLock code that consists of several functions. In the example below, the XOR key used is 0x6B130E06 and the size of Part 1’s is 0x45C.

The rest of the code (Part 2), as well as the contained original file, remain encrypted at this point.

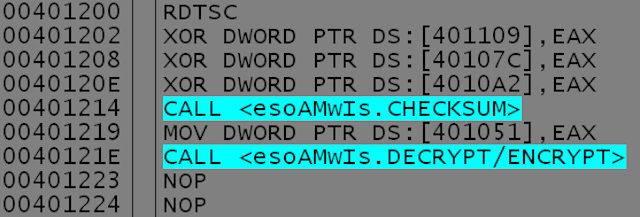

An interesting feature of Win32/VirLock is that the body of (nearly) every single one of its functions is also encrypted and contains a decryption stub at the beginning. This complicates analysis of the malware, as none of the functions’ relevant code is visible in a disassembler. The function encryption is again simple – a checksum from the decryption stub is calculated used as the XOR key to the function’s body.

To make things more fun, after the function’s execution, its body will be encrypted again. The key will be different, however: as shown in the code snippet below, a few garbage instructions within the decryption stub are XORed with a random number (from RDTSC), thus effectively changing the checksum that’s used as the key.

This is the first part of VirLock’s polymorphism – as it executes, its functions are effectively changing in memory as they decrypt and re-encrypt themselves. And the memory ‘snapshot’ modified this way contributes (more polymorphic levels to follow J) to the virus’s uniqueness in each infected file.

The code that makes up Part 1 also contains another decryption function that’s used to decrypt Part 2 and the embedded host file. This third type of decryption is only slightly more complex than the previous ones in that it uses ROR in addition to XOR. The decryption keys for the embedded file and for Part 2 are hard-coded.

To summarize, we have encryption at three levels:

- Part 1 of the code is decrypted by the XOR stub in the beginning

- Part 2 of the code is decrypted by a function within Part 1

- Nearly all functions within the virus code (both Part 1 and Part 2) have their bodies encrypted. They are decrypted as they execute and are re-encrypted afterwards

So how exactly is the code polymorphic? At one point in the malware’s execution after Part 1 and Part 2 have been decrypted, it copies its whole body into a block of allocated memory. Remember: the functions that have executed before this in-memory copy was created have been re-encrypted with a different key. This copy will be used to infect the other files, with the following modifications for each one of them.

Working backwards through the individual layers, the copy is encrypted again. First, Part 2 and the host file being infected are encrypted using randomly generated keys. The encrypted host file is appended to the in-memory copy and the new encryption keys, memory addresses and offsets are written to the Part 1 code, so that it will be able to extract Part 2 and the original file when the new sample is run.

Then the modified Part 1 is encrypted with XOR with a randomly generated DWORD, which gets written to the XOR stub in the beginning.

Finally, the XOR stub builder is constructed randomly as described above and the XOR stub is overwritten with garbage bytes.

After all these steps, we end up with an encrypted copy of the virus in memory with the original file embedded. This is then written to the hard drive in place of the original file. If the original document was not an executable (.exe) Win32 PE file, the „.exe“ extension will be appended to the filename after the original extension and the original file will be deleted. The newly created infected file will also have the icon of the original host.

Conclusion

ESET's LiveGrid® telemetry shows that the number of victims of this new virus is relatively low and that for now the scale of this threat is nothing like that of TorrentLocker or other widespread ransomware. Nevertheless, looking at the transactions associated with the Bitcoin addresses used by the malware reveals that some victims of this fraud have already paid up. We will continue monitoring the evolution of this new ransomware strain.

What makes this ransomware stand out, however, is the fact that it is a functional polymorphic parasitic virus. Our analysis of the code has shown that the malware author has truly played around with this venerable means of writing computer virus code.